Public opinion reflects this unease. A recent Atlantic Council survey found that nearly 7 in 10 Americans believe a major war between global powers could erupt within the next decade. Since the end of the Vietnam War, when conscription was officially abolished in 1973, three generations of Americans have grown up without the draft. As a result, many are unfamiliar with how the system actually works. However, the government maintains detailed plans to swiftly reinstate conscription if the national security situation demands it.

Inside America’s Draft Pool: Who Could Be Called?

To understand the mechanics, it’s crucial to know who is eligible. The Selective Service System currently keeps records on about 16.4 million men aged 18 to 25 across the country. In comparison, active-duty military personnel across all branches number around 1.3 million. If a draft were initiated, men at age 20 would typically be the first group called, followed by others as military needs evolve.

Who Exactly Could Be Drafted if America Faces World War III?

The draft’s reach extends broadly. It applies to U.S. citizens and many non-citizens alike—including permanent residents, refugees, asylum seekers, and even unauthorized immigrants. The system includes individuals with disabilities and transgender persons assigned male at birth. Personal beliefs—whether political, religious, or conscientious objections—do not affect registration eligibility. While only men are currently required to register, military officials have confirmed that the Selective Service is prepared to enroll women should laws change in the future.

From registration to selection, the draft process involves multiple stages of evaluation—ensuring the military calls upon those it needs most in a crisis.

How to Register—and the Serious Consequences of Not Doing So

Registering for the Selective Service is straightforward. The official website serves as the primary portal for registration, and physical forms are also available at roughly 35,000 post offices nationwide. By law, all eligible individuals must register within 30 days of turning 18—a requirement that nearly everyone meets.

But failure to register is no small matter. It’s a federal offense punishable by up to five years in prison and fines reaching $250,000. Beyond criminal penalties, a felony conviction for non-registration can lead to the loss of important civil rights, including the ability to vote and legally own firearms. Additionally, those who don’t register risk losing access to federal jobs, financial aid for college, and in 31 states, even state-sponsored student aid programs. These legal and administrative measures form the backbone of the draft system, ready to be enforced if Congress declares a national emergency.

The Road to Draft Activation: What It Would Take

If the nation ever faced a crisis severe enough—like a global war—the draft would only be triggered after a specific legal process. Both the President and Congress must agree to activate conscription by amending the Military Selective Service Act. Once authorized, the Selective Service System has up to 193 days to transition from maintaining registrant records to actively calling people to duty.

This carefully structured timeline ensures the country can mobilize rapidly while maintaining legal oversight and public transparency.

How Would the Draft Lottery System Work?

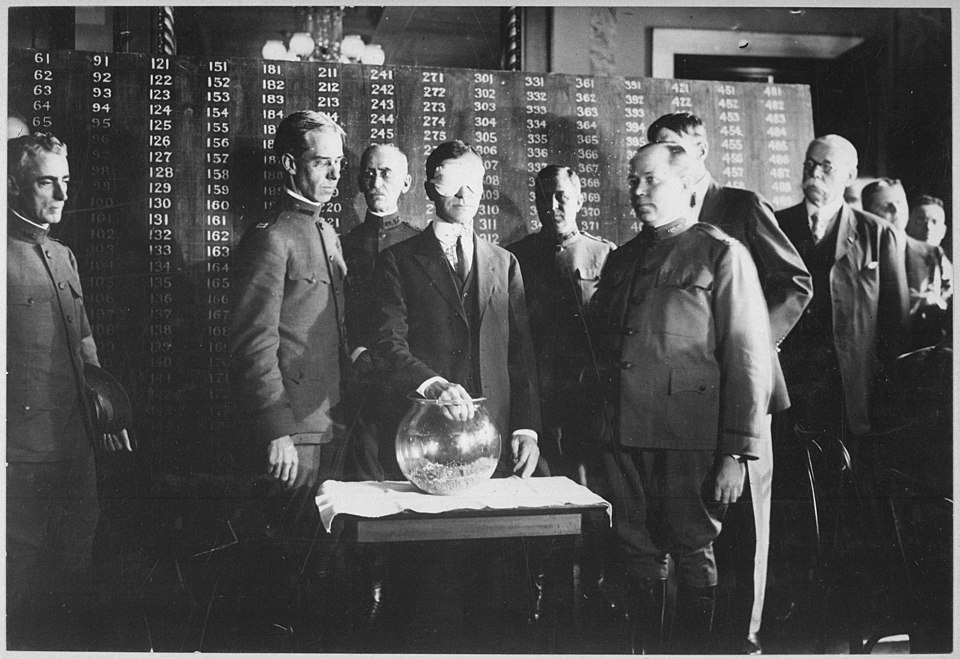

In the event of a draft, officials would hold public lotteries where birthdates are randomly selected—events that are broadcast live on national TV and streamed online to ensure transparency. Each day of the year corresponds to a number between 1 and 365, continuing the method used during the Vietnam War draft lottery in 1969.

Those with lower lottery numbers are called first. Initially, men turning 20 in the lottery year would be summoned, followed by those turning 21, then 22, and so on, up to age 25. If needed, later rounds could include men turning 18.5 or 19. The lottery system also ensures fair geographic representation by selecting draftees proportionally from every state and U.S. territory, balancing urban and rural populations.

Under full activation, the Selective Service database holds several million potential draftees—but receiving a draft notice is just the beginning, not the end, of the process.

From Draft Call to Active Duty: What Happens Next?

Once individuals receive induction orders, they undergo a thorough evaluation at Military Entrance Processing Stations (MEPS). Here, candidates face comprehensive medical and psychological testing to determine fitness for service.

College students can apply for deferments, delaying their service until they complete their degrees. Family circumstances also play a role: married individuals with dependents may qualify for exemptions or be assigned to alternative service roles.

Medical, Psychological, and Legal Exemptions

Not everyone called will end up in uniform. Historically, medical and mental health screenings have disqualified over 40% of those initially drafted. Tests include blood work, vision and hearing assessments, physical fitness evaluations, and psychological screenings, which can take several days to complete.

Conscientious objectors—those opposed to combat service on moral or religious grounds—may be assigned to non-combat roles such as civilian support, administrative duties, or medical positions, per established protocols.

What Military Roles Might Draftees Fill?

Draftees often have some say in their assignments. Many seek roles outside direct combat, choosing specialties in administration, communications, logistics, and other support functions—areas historically requiring far more personnel than frontline combat roles.

What Are the Chances of an Actual Draft?

Despite detailed planning, it’s important to remember that the U.S. military remains an all-volunteer force since the draft’s end in 1973. During the Vietnam War, about 2.2 million men were drafted, though many received deferments or alternative assignments.

Today, federal law still requires men ages 18 to 25 to register with the Selective Service, but this is separate from an active draft. History shows that deferments and exemptions significantly reduce the number of individuals ultimately called to serve. If a draft ever resumes, the actual number inducted into military service would likely be far smaller than initial registration figures suggest.